(article originally written for Mark Deniz’s

“Monster Appreciation Month”)

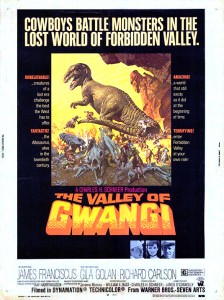

I first saw The Valley Of Gwangi in 1973 or 1974, well after its 1969 release. I was about 5 or 6. It remained my absolute favourite film of all time until I saw Ken Russell’s Tommy (1975) a year or two later.

I first saw The Valley Of Gwangi in 1973 or 1974, well after its 1969 release. I was about 5 or 6. It remained my absolute favourite film of all time until I saw Ken Russell’s Tommy (1975) a year or two later.

I went on a summer afternoon. My older brother took me. Sean was my advisor in all things marvellous and adventuresome, and it’s possible that, were it not for his influence, I’d be an accountant at some fertilizer company, rather than day-in, day-out trying to build castles in the sky – or outer space – and make a living in them.

We lived in Minot, North Dakota then, Minot Air Force Base, a main base for the Strategic Air Command’s B-52 deterrent. A cold, cold place in a cold, cold war. My dad’s day job was to fly in the belly of a B-52 across the Pacific Ocean to the Soviet Union, say hi, hang a louie, and then return home – ideally without receiving orders to continue into the Asian continent toward targets whose names were conveniently located in the seatback pocket in front of him (a seatback pocket with a couple padlocks on it, of course). Yes, just like in Dr. Strangelove (1964). In those days, the USSR and the USA had both made a commitment to send the planet back to the prehistoric era, providing certain eventualities came into being.

While my dad plowed the skies in a bomber heavy with thermonuclear weapons, I was hitting the peak of dino-fever. Dino-fever is like chicken pox – almost every child catches it. If you don’t manage to catch it until you’re an adult, well, it can be quite dangerous and cause you to develop weirdness. I caught it early, but have never recovered from it. The world of the early 1970′s conspired to make my dinosaur baptism vivid and indelible. It was at this same time that National Geographic published a set of four high-quality hardback children’s books. One of them was simply called “Dinosaurs” – the others in the set were about killer whales or spiders or some stupid thing. The book featured dramatic prose descriptions of Mesozoic life, illustrated by paintings done by National Geographic veterans. It was the time of the Sinclair Oil dinosaur – ubiquitous in the American prairie states. And it seemed so marvellous to me at 5 years old that something as serious and grown-up as gasoline station should fly high a brontosaurus mascot. And it was the time – oh, most marvellously – of Aurora’s “Prehistoric Scenes” model kits. Aurora’s scarlet-plastic Pteranodon model, featuring an optional torn wing for super-realistic dino-combat, was the first of many of those kits that I longed for and collected and fussed over and played with until they were plastic shrapnel.

I suppose the screening must have been a special kids show at the base theatre. We walked there over baked brown grass under a sky cross-hatched with vapour trails and punctuated with sonic booms. I insisted on calling the movie “The Valley of THE Gwangi”. He wasn’t just any Gwangi, he was THE Gwangi. And maybe I thought it scanned better than “The Valley Of Gwangi”. Kids make music naturally, and dinosaur movie titles have always been the best playground for the poetic alchemy of childhood – “The VAL-ley OF the GWAN-gi”. Gwangi was majestic and eternal – he deserved poetry. I think I called it “The Valley Of The Gwangi” until I was confronted with seeing the original movie poster in my mid-20′s and just couldn’t for the life of me find a second article in there.

Cowboys and dinosaurs. There could have been no better movie experience in heaven or earth. When you’re very young, you’re inclined to swallow everything you see onscreen, but Ray Harryhausen’s prehistoric beasts seemed to me – even at that young age – TRUE. I had the thought “Yes. That’s exactly right. That’s exactly the way dinosaurs are supposed to look and move and sound.” Of course, in reality, it’s not. Harryhausen’s dinosaurs don’t really even match the paleontological knowledge of the day. In fact, during production, there was even a certain amount of vagueness over whether Gwangi was a Tyrannosaurus Rex or an Allosaurus. But the dinosaurs in Gwangi seemed to correspond to what was in my imagination, and that is always the most important thing in filmmaking – reality not as it really is, but how we deeply believe it is. Ray Harryhausen’s creations weren’t lumbering, walnut-brained juggernauts. They lived, they burned. They were hungry. Even the choice of making Gwangi’s skin color a deep indigo gave him an extra edge, a uniqueness, a personality.

That The Valley Of Gwangi appears to be a remake of King Kong (1933) should be no surprise considering the film was originally a project by Ray Harryhausen’s spiritual forerunner, the special effects genius Willis O’Brien, who created all the ground-breaking effect for King Kong. Willis’s original idea had cowboys finding dinosaurs in the Grand Canyon, rather than the semi-mythical Mexican wasteland in the final film. Willis O’Brien didn’t live to see the completion of Gwangi.

The Valley Of Gwangi was filmed in Spain and a certain European flavour rubbed off on the movie. The old gypsy crone and her dwarf son are elements out of the Old World, quite bizarre in a Mexican setting and Gwangi’s appearance in a bull-ring carnival show, which also features an elephant, definitely doesn’t feel like Mexico.

The film’s conclusion, featuring Gwangi hunting down our heroes inside a cathedral – not to mention the finale of his spectacular, operatic demise by fire – is among the best endings of any monster movie ever made. And the symbolism of the church against an ancient dragon certainly comes out of Old World Catholicism.

The film’s conclusion, featuring Gwangi hunting down our heroes inside a cathedral – not to mention the finale of his spectacular, operatic demise by fire – is among the best endings of any monster movie ever made. And the symbolism of the church against an ancient dragon certainly comes out of Old World Catholicism.

The Valley Of Gwangi was THE dinosaur film until Spielberg’s monster-masterpiece Jurassic Park (1993). Perversely, I avoided Jurassic Park when it was released. I finally saw it projected, almost a year later, at the New Beverly Cinema in L.A. The New Beverly is beloved. It’s a beautiful old temple. But state-of-the-art viewing experience is not what comes to mind when you think about filmgoing at the New Bev. I was knocked out by Jurassic Park, even on the coke-splashed screen at the New Bev, with its inferior sound system and seats like something out of a WWII-era cargo plane. But I bought the deluxe CAV laserdisc set soon after and watched the movie relentlessly.

Spielberg directly lifts Gwangi’s introductory scene moment for moment in Jurassic Park. In The Valley Of Gwangi, the cowboy explorers are chasing an Ornitholestes – indistinguishable, in movie terms, from Jurassic Park’s Gallimimus – and suddenly the film’s eponymous carnivore pops out of nowhere and snatches the fleet-footed animal up in its jaws. Our first daylight glimpse of Jurassic Park’s Tyrannosaurus Rex mimics the moment beautifully, with the T. Rex bursting into the open and snatching up a Gallimimus.

What perverse inner quirk – like a chip on my shoulder – kept me from seeing Jurassic Park when it came out? That movie had been made for me and there was no doubt that it was going to deliver the Mesozoic goods. I can only guess that I couldn’t bring myself to let go of Gwangi, my first great love.

One last “Gwangi” confession: When I was a teen, and a rabid RPG gamer, I ran a Boot Hill “Valley Of Gwangi” adventure. Boot Hill was TSR’s Wild West pen & paper role playing game. I firmly believe I am the only person alive to have run a Boot Hill “Valley Of The Gwangi” RPG adventure.